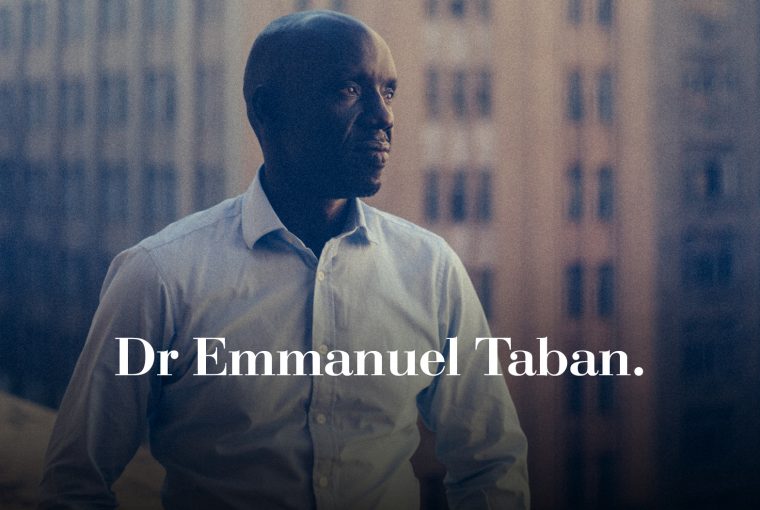

The only way to grasp the magnitude of Dr Emmanuel Taban’s contribution to our lives and to do justice to his remarkable journey in this short blog article, is to create a script for a documentary condensed into a series of visual frames. It would make no sense at all to simply show a snapshot of a boy of 16-years-old fleeing for his life from civil war in South Sudan, and then cut to a tall, smiling man in cap and gown graduating with top honours as a medical doctor and who is now a leading pulmonologist in South Africa. It is too much of a stretch, too wide a chasm without a mosaic of images.

Our first scene opens with the image of a bright, energetic boy with an enquiring mind, from the small village of Loka Round in South Sudan. We see him foraging in the bush for flying ants and locusts mashed with the ashes of pumpkin leaves and eaten with relish, a much-loved grandmother guiding his survival skills. We cut to his mother, divorced, raising Emmanuel and his siblings with every ounce of her strength and ingenuity. They are subsisting, this small family, but there is a peace to the scene. The soundtrack is laughter, his mother’s chiding at his antics, the bleating of goats and running feet in the dust. They are Emmanuel’s feet. He runs errands. Runs to school. Runs to play soccer with a makeshift ball. Runs to buy bread and return with his cache. He has a kinetic energy, coiled and released on everything he tackles.

He pours over schoolbooks with intensity, sucking up knowledge as if it was his very lifeblood. This is a scene that hints at the future. A glimmer of the scholar and medical specialist he will one day become, but as in all films, there is foreboding to the scene. His path from village to international recognition as a doctor cannot be smooth. No script will allow a story to unfold without conflict. And it comes. The scene shifts to destruction, opposing military forces, Sundanese against Sundanese, child soldiers, the burning of huts, the greed of politicians.

The boy Emmanuel is barely in his teens when we see him detained and tortured, bamboo wedged between his fingers, which are crushed until he cries out … but he will not confess to their accusations that he is a spy. In his flight away from his torturers and conflict, we see Emmanuel alone on the road, walking up to 40 km per day, using the bush lore he learnt as a young boy to survive off the land and escape wild animals. But as we see in scenes to come, it is not the bush predator he should fear, but his fellow humans.

This is an ingenious boy, a dragonfly flitting from one opportunity to another, making just enough to survive and move on. He has no papers, a boy stripped down to his will to survive and his quest for knowledge. He is hungry for days at a time, a step away from death. In a single spoken sentence, we hear why he is so driven. What if, like so many of the boys who were sent to fight and never returned, he was to die at the roadside, discarded, perhaps given only a makeshift grave or eaten by hyenas and his bones scattered? He will not accept this obscure fate. It is this indomitable spirit that will carry him thousands of kilometres south, closer and closer to the final scene at the height of a global pandemic where he will make his mark.

Emmanuel meets strangers who rob him of his last pennies. He meets strangers and finds kindness and shelter. He finds rejection in family who might have eased his way, but acceptance, compassion and generosity in the Catholic missionaries who see in this bright spirit what could be.

In this broken journey, Emmanuel remains true to his single most powerful belief; that education is the only way forward, the only way upwards.

From his home in South Sudan to South Africa, an 18-month journey through the borders of six countries, he is at times a ghost of a boy whose family were to discover only much later that he’d survived and thrived. He would ultimately return to South Sudan to introduce them to his bride-to-be and their first-born child.

There are moments at every stage of Dr Emmanuel Taban’s journey that are heart-stopping. There are moments so near to disaster that it seems impossible he would escape unscathed.

But for now, there is one more chapter.

At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic and as a leading pulmonologist, he performed bronchoscopies on patients who were hanging by a thread to their lives. Dr Taban believed his intervention would work, controversial, and against the usual ‘protocol’ that it was. To date dozens of patients owe their lives to him, this driven man who walked Africa to save them, a man who believes that passion, determination and education underpins his success. To that we may add what all doctors swear to uphold: ‘to respect the hard-won scientific gains of those physicians in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.’ This is his gift to us all.

Dr Taban’s book The Boy Who Never Gave Up: a refugee’s epic journey to triumph. (Jonathan Ball Publishers) has been republished twice this year.