As we’ve turned the page on 2018 and entered 2019, there are three core pervasive themes that underpinned the property market last year, all of which may have significant implications for future trends.

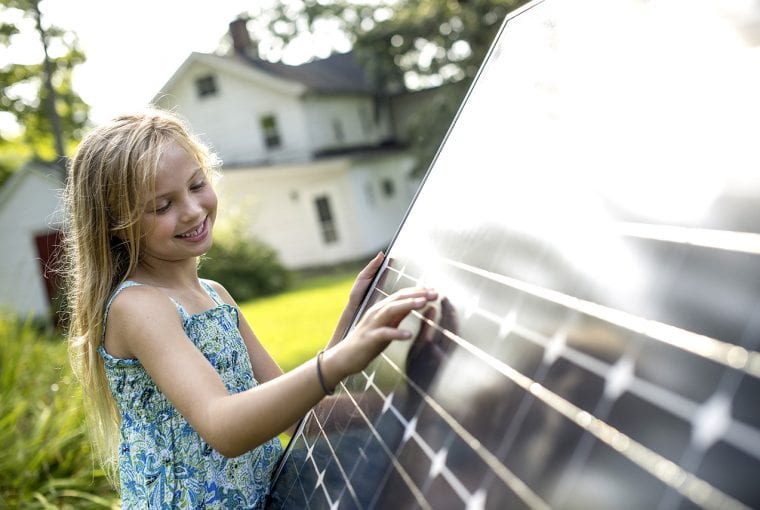

The first of these, says Carol Reynolds, Pam Golding Properties area principal for Durban Coastal, is that eco-friendly living is becoming more and more commonplace, and indeed necessary, as we become more mindful of reducing our carbon footprint and adopting a more sustainable way of living.

According to a recent survey by SAPOA on office buildings in South Africa, green certified premium and A-grade offices had a vacancy rate of just 4.9% (compared to 8.3% for premium and A-grade offices without eco-friendly features) and enjoy a premium on asking rentals of 76%. (SOURCE: SAPOA Office Vacancy report, July 2018). This means that eco-friendly buildings are not only in demand from a residential perspective but also in the commercial space.

In South Australia, Tesla has plans to build the world’s largest virtual power plant in a project which involves installing solar panels and a Powerwall battery on some 50 000 social and low-income homes over the next four years. Good news is that home owners will not be charged for the installation, which will be financed through the sales of electricity generated by their newly installed solar panels, while this system is expected to reduce residents’ energy bills by about a third.

In the USA and UK battery storage of homes with ‘time of use’ tariffs are highly appealing to home owners, as instead of paying more at peak times, they can draw power from their batteries powered up by solar panels during the day. When prices fall overnight, they can use the grid to charge up their electric vehicles.

Says Reynolds: “Secondly, as illustrated by initiatives such as these, the economic landscape has resulted in consumers reducing expenses and finding more cost-effective ways to live. Finally, finding solutions to housing shortages across South Africa is an ongoing need.

Sustainable building

“Within this context, unique and sustainable building methods may provide an all-encompassing, broad-sweep solution to address all three issues. So let’s explore a few of these options in order to ascertain whether or not they are indeed viable.

“There are several companies that have taken the initiative, specialising in smaller repurposed accommodation at a fraction of the cost of standard building methods. Umnyama Ikhaya manufactures off-the-grid, self-sufficient container homes which are transportable to any address within the country. These homes are essentially 30m2 pods, which can be designed to accommodate either two sleeper or four sleeper floor plans. In addition to these standard modules, customised homes can be created by using this modular system to stack units on top of each other or side by side.”

The standard 30m2 units cost R400 000 and come fully equipped with off-the-grid solar panels, batteries, inverters and gas appliances. In addition, they have rainwater tanks, solar pressure pumps and waterless, extracting dehydration toilets. The result is a low cost and environmentally-friendly housing solution which can be adorned to create a funky, fresh look that is becoming increasingly fashionable across the globe.

Says Reynolds: “Indeed, Australia pioneered container homes and many of their container solutions have become part of a growing architectural trend. Ironically, what began as an affordable housing solution, has mushroomed into a growing design trend, with world-class architects incorporating containers into their design language. The result has been a plethora of multi-storey contemporary homes with unique ‘industrial’ features that set them apart from their conventional neighbours.

“At face value, prefabricated, container homes would appear to be the perfect solution for South Africa: quick turnaround times; economically viable; and perhaps most importantly, eco-friendly. So why has this trend not gained traction?”

The issue might well be that the banks have not yet embraced this building philosophy. Nedbank, for example, would look at a mobile home financing package as follows: the land cost, which would be subject to standard mortgage financing criteria for vacant land, and the ‘container’ home cost, which would be viewed separately. Thus, the land financing would require a loan-to-value ratio of 50%, which would mean that buyers would be required to raise deposits of 50% of the value of their land. The homes would then be regarded as ‘mobile’ and so the banks would need to get creative about financing same. One innovative suggestion could be that banks consider financing containers along the same lines as vehicle financing. Another is that in order for the banks to overcome the issue of ‘mobility’, they would be stringent about the ‘permanency’ of the container – for example, is it embedded in concrete, so that it cannot be easily uplifted from the land?

According to Linda Rall of ooba, based on feedback received from the banks, both Standard Bank and Absa have advised that they are not currently able to bond these structures as they fall outside their acceptable security requirements. FNB is open to considering financing options, but they have several strict criteria, for example: the container home is to be fixed to a normal foundation footing/slab; the building needs to have complied with National Building Regulations and Municipal By-Laws; and they will also assess the costs and benefits of using alternative building methods versus conventional ones. FNB will also consider developments provided that all banks work together and jointly approve the product in the proposed development. In addition to the above, technical requirements like NHBRC registration, and the use of an accredited professional team of builders and engineers are essential.

“The rationale behind these somewhat unusual lending criteria, is that the banks may be unsure about the longevity of these housing solutions. Whereas traditional bricks and mortar homes have stood the test of time, and if anything, appreciate in value over-time, the banks may be of the opinion that prefabricated homes do not have a life-time guarantee and may in fact, depreciate over time, says Reynolds.

More creative solutions needed

“In addition to the limitations imposed by the banks, our municipalities do not appear to condone unusual building methods, and as a result, town planning divisions often fail to pass plans for projects that propose more environmentally sustainable, economically savvy, building options. A classic example of this is wooden homes. The use of modular, pre-engineered wooden homes is common-place in countries like the USA and Indonesia, yet in South Africa, and more particularly, in KwaZulu-Natal, wooden homes are simply not allowed to be built in many suburbs. This is perhaps a legacy from the past where wooden homes were deemed to be ‘rural’ and not in keeping with more sophisticated, affluent suburbs. Again, this archaic mentality needs to shift to embrace a more modern, egalitarian view. Our sub-tropical KZN coastal belt provides the perfect landscape for the development of beautiful wooden beach homes.

“Perhaps the solution lies in government endorsing some forward-thinking, progressive developers to take the lead and roll-out projects that make modular homes funky and functional and most importantly, financially viable, by having end-user financing options pre-packaged by the banks from the outset.

If you, like us, think that sustainability starts at home, read more on this growing trend here.